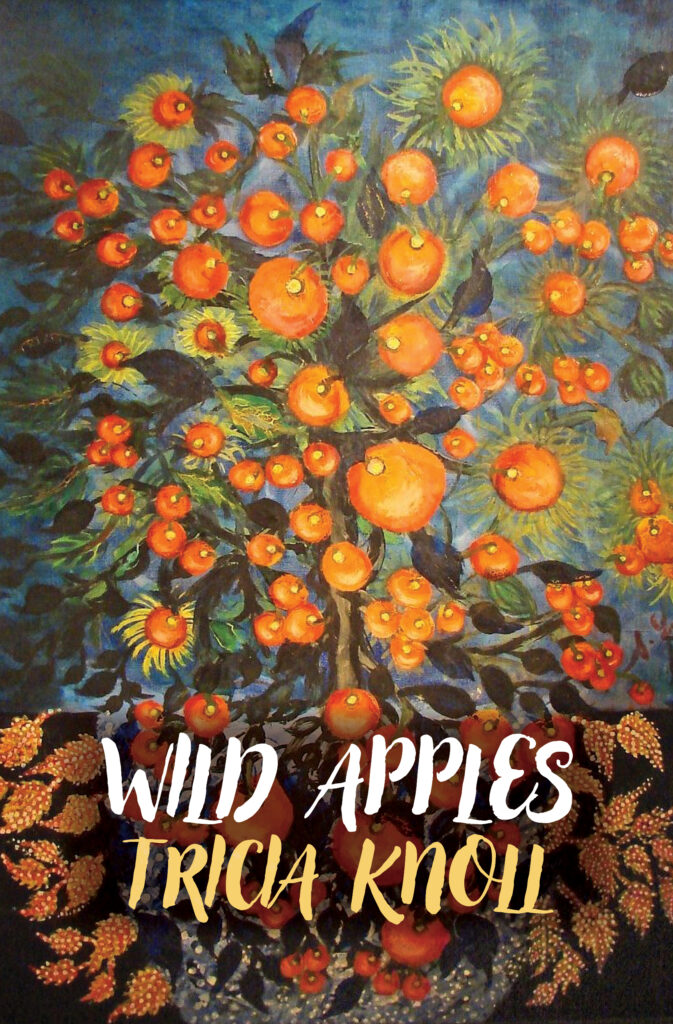

Wild Apples is now out from Fernwood Press. Wild Apples are hard fruits left in abandoned orchards. Like rock walls, a symbol of New England where poet Tricia Knoll found a home in the Vermont woods just before the pandemic locked down. She begins the book with downsizing to make her move from Oregon. Then her poems tell of both loneliness and wonder at the birth of grandsons who live just down the road and the wildlife that moves through her five acres of land. Now available at Amazon and your favorite bookstore.

Poets’ reviews of Wild Apples:

“The bones of this land are not mine,” writes Tricia Knoll, longtime Oregon poet moved to the woods of northern Vermont, but inWild Apples the reader sees the poet begin to make it her own. Here she awaits and then welcomes a first grandchild, telling him what she holds sacred: milkweed, horses, dogs…and the list ends with poetry and songs by people who tell the truth. This poet has brought with her the gift of telling truth with beauty.

Penelope Scambly Schott, Past recipient of the Oregon Book Award for Poetry and author ofOn Dufur Hill

I laugh with Knoll’s humor, wit, imagination and sly cultural critiques—discarding the body, but keeping a doll”s head and stitching it with white dog hair to look more like the speaker. I find balm in the sense of connection to family, friends, and those unmet: the previous homeowner, the Native Americans who never willingly ceded their lands; the flora and fauna, even gravel, dirt and potholes, since the road is in me,/I am not lost. To ending the book with a wonderfully unanswerable question, Which where emerges/at the end of when?, I can only say: Bravo!

April Ossmann, author of Event Boundaries

While reading Tricia Knoll’s WILD APPLES, the latest of her five volumes of poems, I was struck by how she transforms the everyday into the luminous by interweaving human lives with their landscapes, whether the American Northwest of Oregon’s coasts or the seasons of Vermont’s forested terrain. The span of the continent becomes a way to examine the span of a life, its history and rhythms embedded in both seasonal and geographic explorations. The move across country becomes a renewal, an acknowledgement of aging, of change in the context of new birth in the grandson born in Vermont under the looming shadow of the pandemic. Along the way, Tricia Knoll’s tribute to Ruth Stone in the poem by that name and her recognition of the poet David Budbill’s significant choice to be a Recluse on Judevine Mountain reinforce what she names in her poem,Thirty Things a Poet Should Know “what you are looking for is not lost/the moon is there, somewhere.” Vermont proves to be rich soil for Knoll as well as for Stone and Budbill even as she acknowledges the limits of what she can claim in “The Newcomer Begs the Land”: “The bones of this land are not mine. . . This forest became mine/through thefts with many names I know.” Both the Pacific Northwest and Vermont’ss Northeast bear evidence of earlier life on this continent. The life Tricia Knoll examines acknowledges this past while turning her face toward the future in “Rowens” when she writes: “We are second harvests, little one, . . .May we be useful, tender, help feed/the world’s hunger despite our acres/of discontent. To ripen into the best/we’re called to be in separate seasons.”

Mary Jane Dickerson, author of TAPPING THE CENTER OF THINGS and WATER JOURNEYS in ART & POETRY with artist Dianne Shullenberger. With Tamra Higgins, she founded Sundog Poetry Center.